6. Echoes of the Transatlantic Past:

Testimonies of Memory and Loss

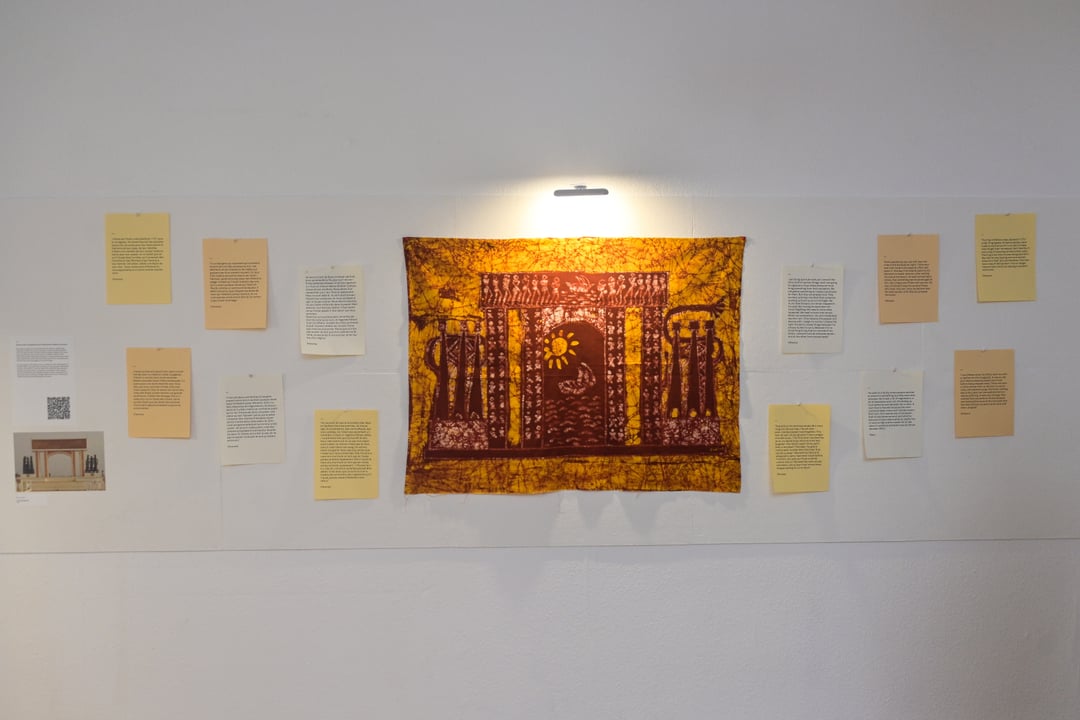

UNESCO Slave Route Step-6: La porte du non retour, Ouidah

DESCRIPTION

This station presents oral testimonies that capture fragmented memories of both sorrow and resilience. These narratives, passed down through families in Ouidah, offer intimate insights into a complex past. Stories uncover accounts of a hidden "sacred" room where slave chains bear silent witness to an agonising history, while other testimonies evoke spiritual rituals that honour ancestors and confront the enduring legacy of a dual heritage.

In conversation with these voices, a painted fabric crafted by local artisans reinterprets the Door of No Return, the final step of the UNESCO Slave Route in Ouidah. Pairing the fabric alongside a photograph of the original doorway establishes an interplay between artistic expression and historical record, inviting a dialogic reflection on how memory and identity are continually reshaped by the past.

Voices of Ouidah: Stories from families recorded by Thierry Boudjekeu, October 2022

1. « Il est allé dans une famille où les gens avaient envie de lui montrer quelque chose mais ils étaient aussi réticents. Donc il a fallu beaucoup de négociations, de discussions et il a fallu mettre en confiance avant qu'on ne l'introduise dans une pièce. Une pièce qui est "Sacrée" parce que la pièce contenait des chaînes d'esclaves et personne n'entre dans cette pièce-là. Donc c'est exceptionnellement qu'on le lui a fait visiter ; et ce qu'il a découvert, c'est des chaînes entassées d'une hauteur de près de deux (2) mètres et il a fait le vœu de ne pas en parler nulle part et que ça restera entre eux. » (Homme)

‘He went to a family where people wanted to show him something, but they were also reluctant. So it took a lot of negotiation, a lot of discussion and a lot of building up trust before he was allowed into a room. A room that is ‘Sacred’ because the room contained slave chains and nobody enters that room. So it was by way of exception that he was shown around, and what he discovered were chains piled up nearly two (2) metres high, and he vowed not to talk about it anywhere and that it would remain between them.’ (Man)

2.« Je suis en train de faire un travail spirituel, donc je consulte le Fâ, pour qu’il me confirme certaines choses. Et je vais organiser un rituel où chacun devra ramener quelque chose de ses ancêtres. Nous allons tout rassembler pour leur faire un sanctuaire. Mais ils sont déjà là. Ils sont là et ils manifestent leur présence, ils nous poussent à agir, à ne pas oublier. Nous devons avancer, ne pas rester enfermés dans le passé. Mais avancer, ce n’est pas oublier. Il faut savoir ce qu’il s’est passé. Il faut savoir qui nous sommes.

Quand je suis quelque part, je ne dis pas tout de suite qui je suis. Je regarde d’abord à qui j’ai affaire. Je pèse les mots, je choisis à quel moment révéler les choses. Parce que c’est lourd à porter. Parce que ce n’est pas anodin de dire que d’un côté de ma famille, je descends d’une esclave, et de l’autre, d’un négrier. » (Femme)

I am doing spiritual work, so I consult the Fâ to confirm certain things. And I am going to organise a ritual where everyone must bring something from their ancestors. We will gather everything to create a sanctuary for them. But they are already here. They are here, and they manifest their presence, pushing us to act so as not to forget. We must move forward, not remain trapped in the past. But moving forward does not mean forgetting. We need to know what happened. We need to know who we are.

When I am somewhere, I do not immediately say who I am. I first observe the people I am dealing with. I weigh my words; I choose the right moment to reveal things because it is a heavy burden to carry. Because it is no small thing to say that on one side of my family, I descend from an enslaved person, and on the other, from a slave trader. (Woman)

3. J’avais quinze ans quand mon père m’a emmenée avec un médium visiter Zougbodji. C’était un ancien port où les esclaves étaient parqués avant d’être embarqués. Il y avait aussi une dame blanche avec nous. Dès que nous sommes arrivés, elle s’est mise à pleurer. Elle ne savait rien de ce lieu, mais elle disait qu’elle sentait une grande souffrance. C’était très étrange. Elle a insisté pour qu’on fasse des rituels, parce qu’elle disait que les âmes des esclaves morts sans sépulture étaient toujours là, prisonnières. » (Femme)

I was fifteen when my father took me with a medium to visit Zougbodji. It was an old port where enslaved people were held before being shipped away. There was also a white woman with us. As soon as we arrived, she started crying. She knew nothing about the place, but she said she felt immense suffering. It was very strange. She insisted that we perform rituals because she believed the souls of the enslaved who had died without a proper burial were still there, trapped. (Woman)

4. Il y a des gens qui racontent qu’on entend encore les cris des esclaves la nuit. Les pêcheurs et les chasseurs de crabes qui passent par là en parlent souvent. Un jour, Fofo Isidore est rentré chez lui en sueur, fiévreux, après être allé poser des filets à la plage. Il disait qu’il avait entendu des voix, qu’il y avait quelque chose qui l’avait effleuré, comme un vent lourd de douleur. Il était convaincu que c’étaient les âmes de ceux qui n’étaient jamais revenus. Ici, on croit que les morts errent tant qu’on ne leur a pas rendu hommage. (Femme)

Some people say you can still hear the cries of the enslaved at night. Fishermen and crab hunters who pass by often talk about it. One day, Fofo Isidore came home drenched in sweat, feverish, after setting his nets at the beach. He said he had heard voices, that something had brushed against him, like a heavy wind filled with sorrow. He was convinced it was the souls of those who never returned. Here, we believe that the dead wander until they are properly honoured. (Woman)

5. L’Arbre de l’Oubli a été planté en 1727 sous le roi Agadja. On faisait tourner les esclaves autour de cet arbre pour leur faire perdre la mémoire de leur pays, de leur identité. C’était une manière de leur couper toute attache avec leur passé. Le roi savait que ce qu’il faisait était terrible, qu’il arrachait des hommes et des femmes à leur terre et à leur famille. Cet arbre, c’était une façon de leur dire : ‘Vous n’avez plus d’histoire ici, vous appartenez à un autre monde maintenant.’(Femme)

The Tree of Oblivion was planted in 1727 under King Agadja. Enslaved people were made to walk around it in circles to make them forget their homeland, their identity. It was a way of severing all ties to their past. The king knew what he was doing was terrible, that he was tearing men and women away from their land and families. This tree was a way of telling them: ‘You no longer have a history here; you belong to another world now. (Woman)

6. Ils nous ont dit que la terre était vide. Mais en fouillant dans les archives, j'ai trouvé des chuchotements, des noms effacés, des vies oubliées. Ce n'était pas seulement un cimetière. C'était un registre d'âmes volées. / La première fois que j'ai touché le tambour, mes mains ont su ce que mon esprit avait oublié. Le rythme n'était pas le mien, mais il vivait dans mon sang. Ce rythme, disait ma grand-mère, est plus ancien que l'océan qui nous a emportés. Elle m'a pris la main et a murmuré un nom que je n'avais jamais entendu auparavant. Elle m'a pris la main et a murmuré un nom que je n'avais jamais entendu auparavant : « Trouvez-le », a-t-elle dit, comme si le temps pouvait être défait. C'est ainsi que j'ai suivi ce nom à travers les continents, pour apprendre qu'il n'avait jamais cessé d'attendre notre retour. (Femme)

They told us the land was empty. But when I dug into the archives, I found whispers—names erased, lives forgotten. This was not just a burial ground. It was a ledger of stolen souls. / The first time I touched the drum, my hands knew what my mind had forgotten. The rhythm wasn’t mine, yet it lived in my blood. ‘This beat,’ my grandmother said, ‘is older than the ocean that carried us away.’/ She took my hand and whispered a name I had never heard before. ‘Find him,’ she said, as if time could be undone. And so I followed the name across continents, only to learn that he had never stopped waiting for us to return. (Woman)